Handmade Prototyping

06.12.2025This is a long post - there’s a funny story as a prize for those who read to the end though

I’ve been attending the Handmade Seattle monthly meetups for a while now, and found myself in the fun position of having worked as a game designer, project manager, and software engineer in a meetup of mostly engineers. Lately there’s been an ongoing conversation of how to achieve the same excellence in UXUI (pronounced ooks-wee, I’m determined to make this stick) design that we aspire to in the technology we build. I’ve been summoned by Abner a few times now and thought it time to put down some (extensive) thoughts in on place.

I’ll spare the usual credentials and self advertising. These ideas aren’t mine, (they aren’t even novel - I simply believe I am communicating them to a fresh audience. And thus I call on the muses of whoever brough quaternions from space flight to games). I can, however, attest to their efficacy.

So without further ado…

Why Not Just Write Code?

I like to think about this by starting with an adage many in the Handmade Community will be familiar with:

“Write the usage code first.”

This is pretty well accepted wisdom, but in my opinion, it’s not about code at all. It’s actually saying:

“Build such that you are confident in your understanding of the person who will use your product later.”

So then the question becomes… “How do I minimize cost, while maximizing my confidence in my approach?”

Cost here is money, time, excitement, buzz, etc.

The cost of building the wrong thing, is that you’ve wasted time and effort, and have to spend more of both to build the right thing.

Confidence means “I know that what I’m building is right”.

At first, I have little (or misplaced) confidence. Therefore, I shouldn’t build anything, lest it end up costing too much. The solution is to invest in cheap “artifacts” that answer questions, in order to build our confidence progressively over time. The process of doing this, repeatedly, is called Prototyping.

How to Prototype, By Example

Let’s imagine we’re making a Deck Building app for a game like Magic: The Gathering, or Pokémon. This is fairly well trod ground - but how would we approach it from first principles, or in the handmade way, doing it from scratch?

Well, in the beginning, I have no idea what this app could look like. I know it’ll need to track cards, and draw them on screen. Save and load a collection, maybe sync to a server. This is all tech I can start building safely - in other words, I have high confidence these pieces are right.

But I have absolutely no idea in what ways I should lay out cards on screen, or what extra information is useful to deck-builders to see, or… This is where we start prototyping!

As a first question, I might ask “How do people build decks?” followed by “What is the fastest, cheapest way I can learn?” In this case, I don’t need to make anything at all! Just head down to my local game store for magic night, and ask a few people if they could show me how they do it! (When I do this for work, we pay these people - you should too, it’s good form) From this ‘prototype’, I might learn that people sort cards into piles by the effect of the card, by color, by synergy, and by cost. Not only that, no two players I watched used the same piles. Additionally, they constantly re-sort the cards into new piles to see different “views” of their deck - what’s the cost curve of their deck? Do they have enough cards of this type? etc.

So now I have a new idea for how to display cards in my app. Users should put cards in named piles. There can be multiple sets of piles, each set containing references to the same cards, but cards inhabit different piles in each set. Switching sets should be easy. So lets build it right?

Not so fast - if that didn’t make you ask new questions, you aren’t paying enough attention. Let’s do another round!

A new question emerges from the tall grass: “Which piles are the right piles?” For example, I know for Magic, I might have one set of piles by color - so Red, Green, Blue, White, Black, Colorless. I might have another set by function - Card Draw, Board Wipe, Removal, Protection, Big Stompy, etc. Are these right? Am I missing any?

How fast can I answer this question with high confidence? One way would be to draw each set of piles on a piece of printer paper - nothing fancy just named boxes. That way you can see all your options. Then, go back to your LGS. This time, we’re going to try and keep our meetings shorter so we can do more of them with more people - 10 minutes tops. Give each person the pages and ask them to take a deck of theirs and sort the cards into the named piles. Then do it again on the next sheet, and so on. I guarantee you will hear things like:

- “This is cool - can we add a pile called X to page 3?”

- “I wouldn’t use that page at all - it doesn’t make sense for reason X, Y, and Z”

- “Why did you draw sandwiches for me to put my cards on?”

- “I don’t use that pile ever” AND “This is the only pile I ever use” about the same pile.

- and best of all: “This doesn’t quite work… Can I have your pen? I just wanna draw this idea for you”

That last one? Pure gold - they not only found something missing in your design, they offered to explain how to fix it!

Now there’s some tried and true wisdom that says “Your players are 100% right about what’s wrong with your design. They are seldom correct when it comes to the solution though”. What this means is that you should take a “suggestion” as “a sign post for something that’s wrong” and think very hard how to solve it on your own.

So now, you’ve returned after 2 days of prototyping and you’ve gained a lot of information. Not only that, you haven’t written a single piece of code. But remember that list of things we could start building, because we were confident they were the right things? Well, now we can add to that list “multiple views of multiple lists of cards”.

And you can continue this way forever. If you do it right, you’ll keep prototyping any time you have a question about what you “should” do next, or how you “should” approach a problem. Over time you’ll gain a better and better sense of the design space you’re working in, and a great deal of knowledge of what works and what doesn’t.

Aside: If you’re smart, you’ll realize that this is a special form of ethnography, and that you should probably be doing a whole hell of a lot of note-taking, and not all your notes should be about your prototypes… but this post isn’t about design research so we’ll leave that for another time.

The Risk of Not Prototyping

What would happen if you didn’t prototype? Well, we’re still approaching this from first principles - we’re Handmade folk after all. So my initial conditions are the same, but this time? This time we’re gonna build baby!

Since I don’t know how people build decks, I might assume that a deck is a list of cards. So I make a way to view lists of cards. Then you click a card and it’s added to a deck. Click it again to remove it. Then you finish up and go to a page where I can see the cards that I need to find to put in my deck.

This is a fine piece of engineering - it renders at 60Hz, has animations and effects. It launches in the blink of an eye. But it’s wrong, and people won’t use it. The concrete ways it’s wrong should be pretty obvious:

- a linear model of deck building (cards go in, then I look at the finished product)

- no way to sort cards already in the deck

- no way to investigate what my deck might be lacking, or have too much of

But the actual problem isn’t that you made something that’s wrong… it’s that you probably spent a few weeks building it! Now, you go to your LGS for the first time, excited to show off your app and… nobody tells you it’s bad, but they very politely stop showing interest after a few minutes. You’ve wasted time and money, and now, honestly, how excited are you to keep working on this anymore?

This is why you should build prototypes!

Analog: Sketching

(I mean, you’re already putting up with me droning on about one of my favorite topics, why not indulge me in one more?)

I have a background in fine art; I studied Illustration in college. Every student at RISD takes the same 3 classes their freshman year - Drawing, 2D Design, and 3D Design. The founders and organizers of RISD believe that it is so important for every artist to be able to draw - from sculptors and painters to graphic designers and industrial designers - that they make everyone devote at least 2 full semester classes to it (and mind you, these classes meet 1/week for 8 hours and assign roughly 20 hours of homework each week - it’s brutal).

You’ve seen sketches everywhere from museums to bar napkins. But what are sketches for? Sketches answer questions about a final piece of art. Each sketch answers a different question, or multiple sketches can be used to explore multiple answers to the same question. They’re basically prototypes - but thousands of years old, as opposed to the tech-jargon-nonsense the term ‘prototype’ has become in the last 40 years (though I did learn prototype was first used in the 1500s, so that’s cool!).

So if there’s ancient knowledge to be gleaned, let us glean it!

Edgar Degas

I love Degas’ sketches, because often times you can see him draw the same limb over and over again from the same figure. There are even a few finished paintings where these marks show through. These are prototypes! Degas is attempting to figure out the right position for the limb before investing in fully rendering it. The thing that strikes me about these is that he knows the sketch is just an artifact - it has no worth other than answering a question. Use it, break it, move on - if your prototype is too precious, you have failed to prototype well.

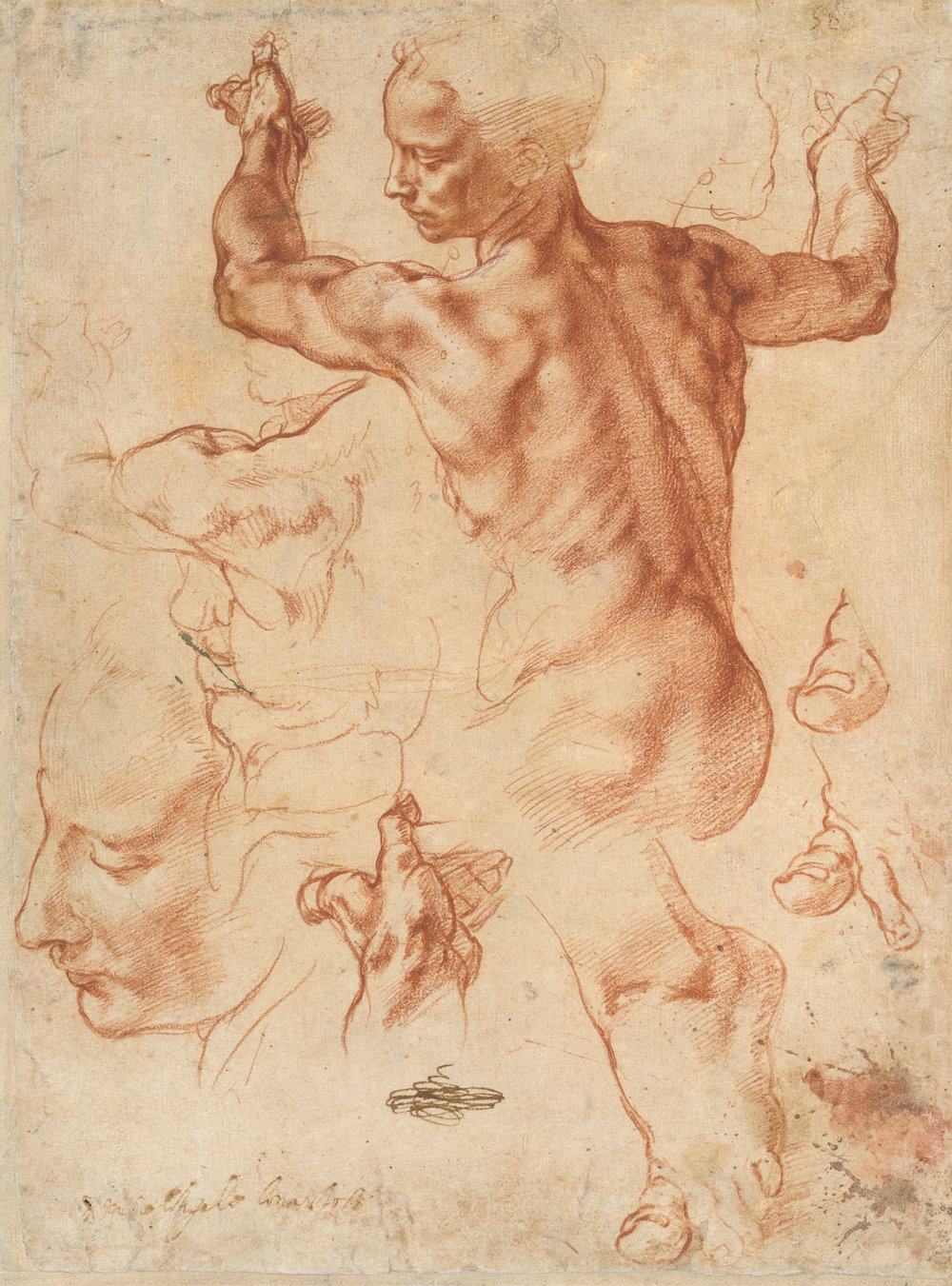

Michelangelo

Whats more costly than re-painting a limb? How about buying a new chunk of marble, and starting over a carving! Or tearing down the ceiling of the Cistine Chapel to begin again? Michelangelo was a master when it came to anatomy, but even he redrew figures to explore posture and musculature before attempting to do a painting or carving. Here we can see multiple attempts at different pieces of anatomy for the same piece. Notice how each section of the sketch is answering a different question: What if the head was tilted just a little differently? What do the deltoid and trapezius do when you bend your arm like this? How effortful can I make this hand look? And it’s all crammed together - there’s no reason not to test many things at once.

What’s even more important to me, is that we see him using a different medium than his final one to prototype in. This sketch was done in red chalk (probably, I’m not an art historian and didn’t dig too deep), while the final piece (what you see below) was painted in frescoe in the Cistine Chapel.

I’m going to get dragged through the network for this but…

Working on understanding an algorithm? Maybe sketch out an implementation in javascript, and ignore memory til you understand what has to happen.

Did you know that you don’t, in fact, have to use software to prototype software?!?!

Pixar

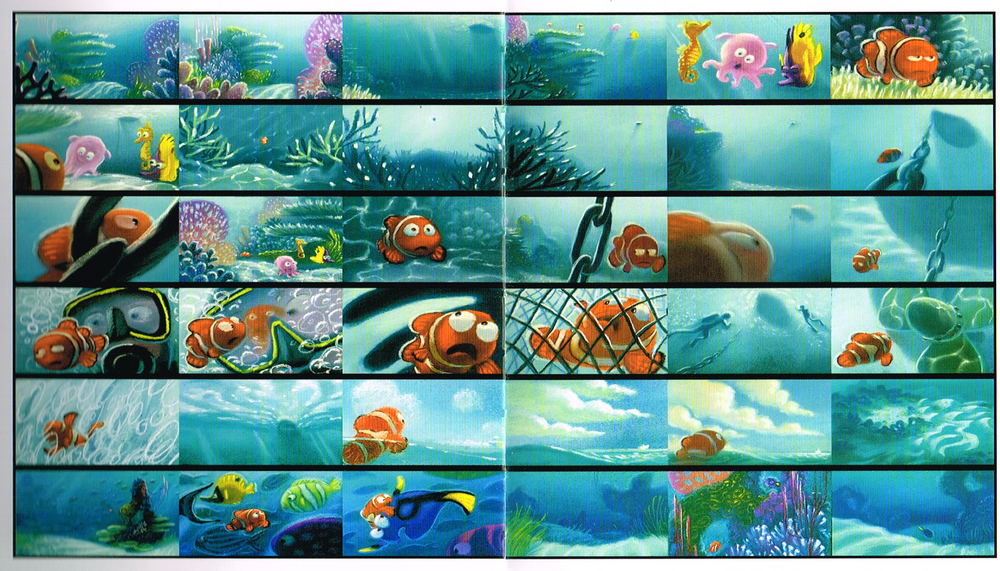

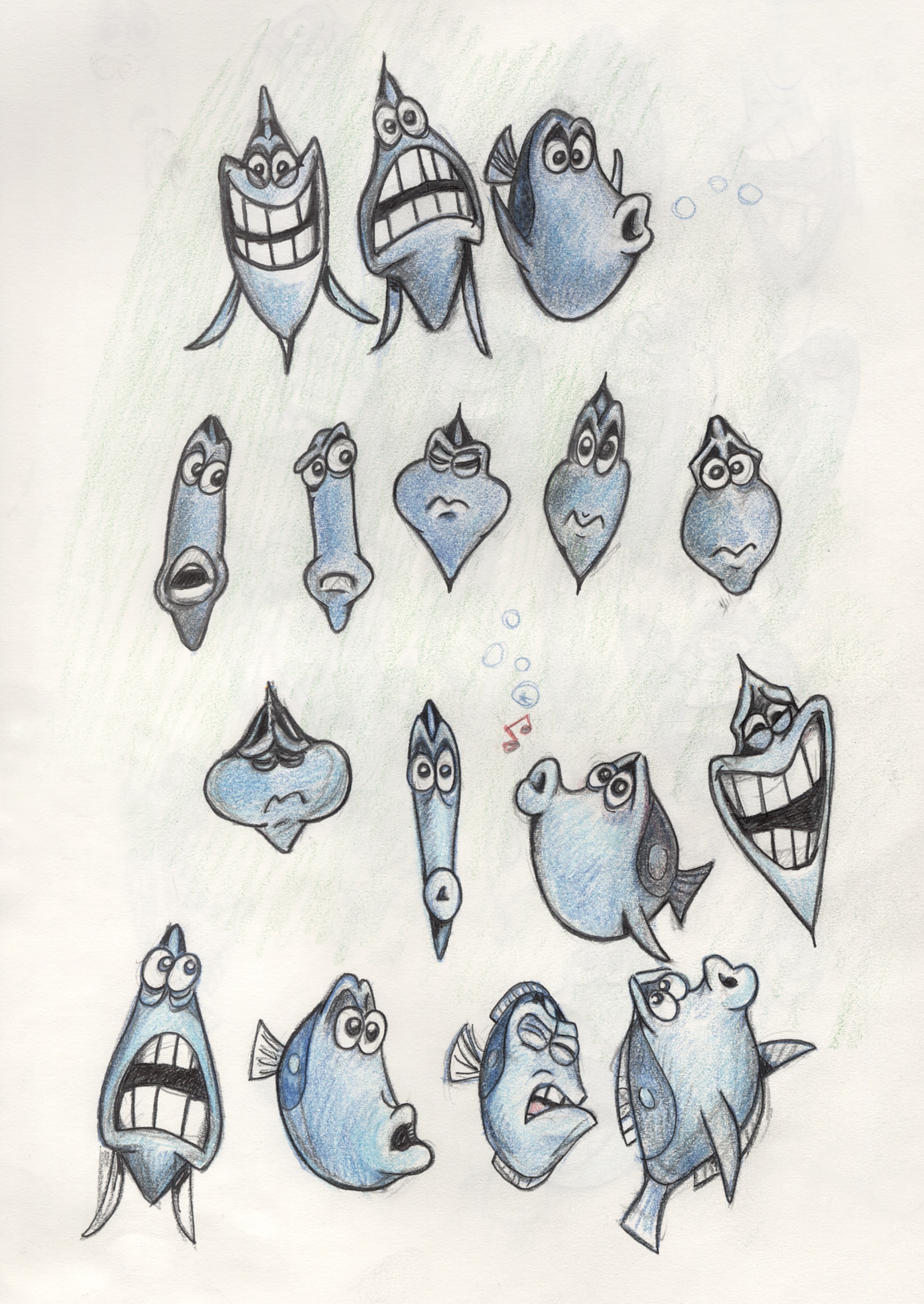

And its not just the old masters. Pixar invests heavily in traditionally trained 2D artists, because you can discover a whole hell of a lot about a character or a scene without modeling, texturing, rigging, lighting, and post processing it.

Here we see a story board - a quick series of sketches to show what a sequence might look like, complete with expressions, lighting, camera moves, even caustics! And it probably took a few hours for a single artist to produce, and only a few minutes for the director to give notes and refine it. Imagine how long it would have taken to change course if they’d tried to make the whole scene for real first!

Similarly, we can use sketches to prototype for a rig! Here, Dory’s expressions are explored so that later, when a technical artist goes to rig her model, he knows the range of what she’s required to do. This not only lets them spend the most focus on the most important “hero” expressions, it also gives them confidence that they aren’t wasting time on expressions or abilities that won’t be used in the movie. Dory’s face could absolutely show anger, but that wasn’t an expression she needed at all in the first movie (I’ll admit I haven’t seen the second). With a few sketches, we’ve cut out potentially days of rigging time!

Prototype Examples

Example 1: The Explorer Lab

My first project after I graduated was to build “A real life magic school bus that takes kids to Mars to learn about engineering”. Our finished product was a West Coast Customs built bus tricked out with TV screen windows, LED lighting, theatre audio equipment and iPads for every student to build their rovers on and drive about the surface of Mars (which they could see out the ‘windows’).

How did we start? I drew a bunch of blobs on a piece of foam core. Gave each kid a length of string and some thumb tacks, and said “Start on this side. Make your string reach the other side. You can’t cross any red areas, and if you cross a yellow area I cut an inch off your string.”

Every kid completed the ‘game’, but that wasn’t what we wanted to see. The real success was that one kid asked “Is the string how for the rover can go? Why is that?” and we had a discussion about battery life, motors, and terrain.

Another asked why he couldn’t just fly over the rocks, and we talked about the upcoming Perserverance and Ingenuity mission.

The questions we were asking through our prototypes were:

- Can we use a game like this to make kids ask questions about engineering?

- Can we deliver real science content through a game with these elements?

The answers were: Yes!

The part I’m not telling here is that we’d already done this 3 times with different game ideas. I had kids tell me they were boring, they hated them, they hated ME (ouch), and that they wanted to go do their homework (super ouch). Learning that our first ideas sucked only took us 2 weeks, and maybe $100 of craft supplies. If we’d gone and built the whole bus with my first idea, it would have been a several million dollar disaster.

Example 2: Design Pitch Decks

Whenever my business partner at PSJR and I do design & development work for a client, we start with a pitch deck. The deck has anywhere from 2 to 6 approaches in them. These are inspirations, fonts, colors, sample applications that we (mostly Jon for this phase honestly) put together quickly. None are precious, and we almost certainly won’t go with any one of them exactly as we present.

The point is to hear how our client responds to the designs. What do they like or dislike? When they say how a direction is wrong, how do they describe the difference between what they see and what they want? Then, when we go away for attempt #2, we can begin investing more in our next directions, safe in the knowledge that we’re no longer shooting in the dark.

Secret Tip: When you have stakeholders, like C-Suite folks or a client who has hired you, showing them your prototypes can be scary. BUT, if you do (and do so in a way that lets them know you aren’t wasting their money), then your client feels like they’ve had a say in your design process and will become more invested in your final output. The way client work ususally happens is that your daily contact is not the decision maker. Your project will receive final approval from some higher up. Having your direct contact fighting for you is a god-send when it comes to defending your work.

Example 3: Paper Printouts

I was working on a fairly boring project building data visualization tools for a global retail chain, to let them see the impacts of their business on the planet. Most of the project was devoted to cleaning up the data from hundreds of municipal power plants, calculating various metrics relating to heat, transport, and overtime, etc. It was gruelling.

But it also meant we had very few engineering resources to devote to actually building the visualizations and reporting tools. So we knew we needed to get it right the first time, and do it fast. Instead of wireframing out complex flows, or building quick react prototypes, we had our designer throw some mock up diagrams together in Figma. Then we went around the company HQ and showed our designs to probably 100 people. After a week of this, we knew roughly:

- what information was extraneous to everyone (and therefore, what our client needed to find ways to make people care about)

- what information people already had, often times in better tools than what we could build

- what information was novel to someone, but mundane to someone else

- what information was useful, just in a different format than what we’d shown

Given our stretched engineering team, these prototypes let us quickly build the tools that would reach the most people. Further, it actually let us stop processing some data, because we found it was already hiding in the company, but our client hadn’t known - this in turn freed up more engineering resources so we could do a better job at the really important stuff.

Example 4: Elmo’s Monster Maker

Remember that prize for reading through I mentioned? You’ve made it! It’s here. This also isn’t a story I was involved in - it’s just legend passed down to me, and now, I pass it on to you.

A long time ago, some people were asked to make iPhone apps for Sesame Street. One was going to be called Elmo’s Monster Maker - the player got to customize a monster on screen, and see it dance with different moves. (It’s for very little kids, nothing complex) But it was very early in the days of the iPhone - the App Store had come out just 3 years earlier. Nobody knew what they were doing. So these folks printed out a huge iPhone picture, cut the screen out, and filmed themselves being goofballs, acting out how the app could work.

This video got them funding to build the app, which was successful enough to continue the partnership which, was still going on at least 5 years later when I got there, and went on for at least 3-4 more. So a decade long business relationship spawned by a video that probably took half an hour to make. Pretty good return on investment right? Here’s the video:

Conclusion

Like I said at the beginning, this is old news. But it’s valuable practice, and can vastly improve your process if practiced regularly.

I don’t think I’m saying very much new, I’ve simply been hanging around in places where I’m consistently asked to bring a perspective on this stuff, so I figured I’d put it in one place. Feel free to ask questions at the next meetup if you’re there.

Addendum: Further Reading

I learned all this through 10 years as a design consultant at IDEO’s Play Lab, but I have two book recommendations. They’re unorthodox for this, but if you’ve never thought deeply about prototyping before, then you probably haven’t thought about the other ideas in these books either. Give them a read:

The Art of Game Design by Jesse Schell

This book has some really lovely chapters on prototyping. It is also the best book on design writ large I’ve ever read. Even though it claims to be about game design. I will die on this hill.

Exercises for Game Designers by Brenda Romero

Disclaimer: I don’t own any of the pictures in this blog post

Disclaimer: I’m not associated with IDEO in any capacity, and don’t represent them - these views are my own